Television has changed dramatically over the decades, and so have audience expectations. Shows that once dominated prime time with their humor and storylines now feel out of step with modern values.

What worked in the past doesn’t always translate to today’s world, where viewers demand more thoughtful representation and sensitivity.

1. All in the Family (1971–1979)

Archie Bunker became a television icon, but his character would spark outrage today.

His openly racist, sexist, and homophobic remarks were meant to satirize prejudice in 1970s America.

However, modern audiences might miss the satirical intent entirely.

The show walked a fine line between mocking bigotry and normalizing it.

Today’s viewers expect clearer moral framing and less ambiguity in messaging.

What seemed cutting-edge social commentary five decades ago now risks being misinterpreted as endorsement.

Networks would face immediate backlash from advocacy groups and social media campaigns.

The nuance required to appreciate the show’s original intent simply doesn’t survive in our current cultural climate.

Even with disclaimers, streaming platforms would hesitate to feature it prominently.

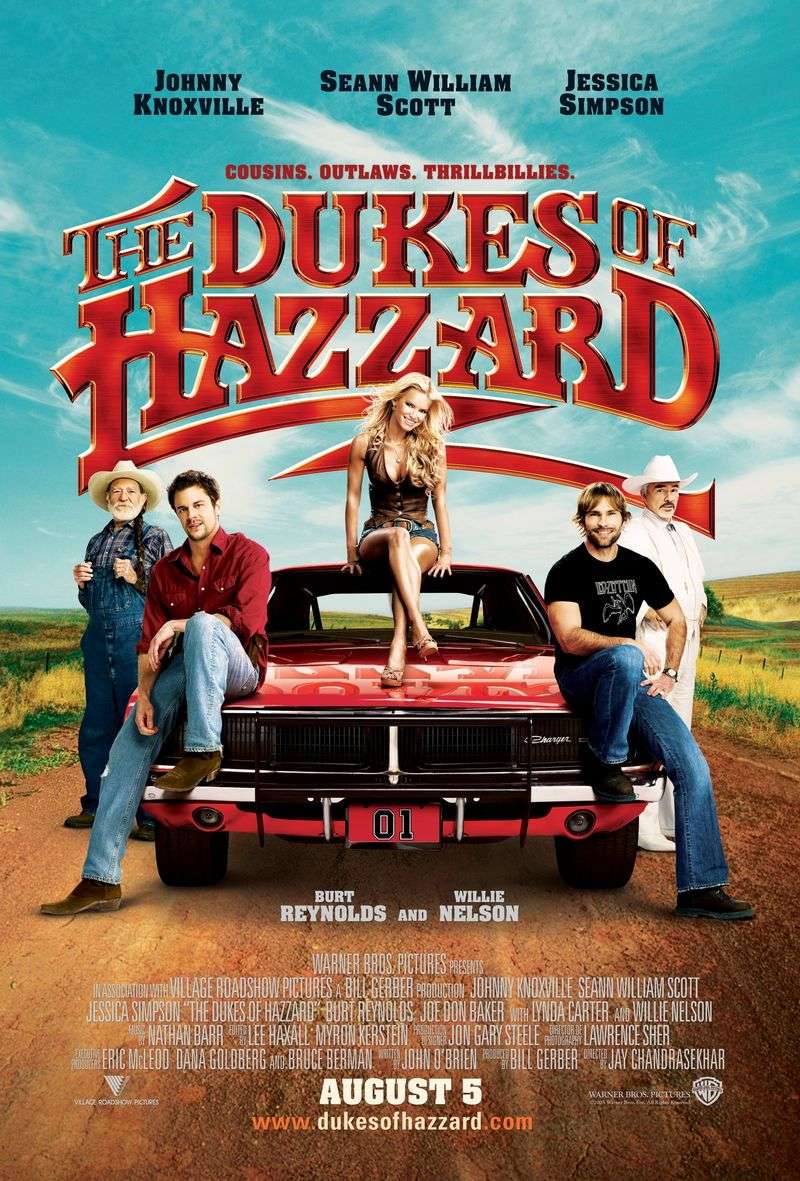

2. The Dukes of Hazzard (1979–1985)

That bright orange Dodge Charger with the Confederate flag painted on its roof defined an era.

But what seemed like harmless Southern charm in the 1980s now represents deeply problematic symbolism.

The General Lee car has become a lightning rod for controversy about heritage versus hate.

Beyond the flag issue, the show presented an oversimplified view of rural Southern life.

Characters lacked depth and diversity, relying on stereotypes that feel uncomfortable today.

Modern audiences expect more authentic and respectful cultural representation.

Streaming services have already pulled episodes or added disclaimers to address these concerns.

A reboot would require completely reimagining the show’s core identity.

Without its most recognizable symbol, would it even be the same series?

3. Three’s Company (1977–1984)

Jack Tripper pretended to be gay so he could live with two female roommates, and that premise fueled eight seasons of comedy.

The entire setup relied on outdated assumptions about gender and sexuality that haven’t aged gracefully.

Jokes about homosexuality as something scandalous or hilarious feel painfully insensitive now.

Misunderstandings about sexual orientation drove most plotlines, treating LGBTQ+ identity as a punchline.

Today’s audiences recognize how harmful this representation was to real people struggling for acceptance.

The show reinforced stereotypes rather than challenging them.

Gender role humor also dominates every episode, with women often portrayed as objects of desire.

What passed for lighthearted fun in the late 1970s now registers as problematic and offensive.

4. I Dream of Jeannie (1965–1970)

A magical genie trapped in a bottle who calls her rescuer “Master” sounds charming until you examine the power dynamics.

Jeannie possessed incredible abilities but spent every episode serving Tony’s needs and wishes.

Her entire existence revolved around pleasing him, regardless of her own desires.

The show presented female subservience as adorable and romantic rather than problematic.

Modern feminism has taught audiences to recognize these unhealthy relationship patterns.

A powerful woman diminishing herself for male approval contradicts everything contemporary viewers value.

Even the costume design emphasized objectification, with Jeannie dressed to appeal to male fantasies.

Today’s audiences demand female characters with agency, complexity, and independence.

The master-servant dynamic at the show’s core simply cannot be repackaged for modern consumption.

5. Bewitched (1964–1972)

Samantha could literally move objects with her mind, but her husband Darrin wanted her to be an ordinary housewife.

The show’s central conflict revolved around a woman suppressing her extraordinary gifts to make her insecure husband comfortable.

That premise feels suffocating through a modern lens.

Episode after episode showed Samantha apologizing for being too powerful or too different.

Darrin’s fragile masculinity couldn’t handle having a more capable partner.

Contemporary audiences recognize this as emotional manipulation rather than romantic comedy.

While the show had charm and humor, its underlying message promoted conformity over authenticity.

Today’s viewers celebrate women embracing their full potential, not hiding it.

A show asking its female protagonist to diminish herself would face immediate criticism for reinforcing patriarchal expectations.

6. The Honeymooners (1955–1956)

Ralph Kramden’s signature catchphrase threatened to send his wife Alice “to the moon” with a punch.

Domestic violence jokes formed a recurring element of the show’s comedy, with Ralph regularly raising his fist in mock anger.

Even as obvious exaggeration, these threats wouldn’t fly today.

The 1950s audience understood these moments as harmless bluster from a frustrated working-class husband.

But modern viewers recognize how such “jokes” normalize abusive behavior and minimize real domestic violence.

Comedy about threatening your spouse has no place in contemporary entertainment.

Beyond the violence jokes, the show portrayed marriage as constant conflict and resentment.

Ralph’s schemes and Alice’s sarcasm defined their relationship more than affection.

Today’s sitcoms present healthier relationship models that audiences actually want to emulate.

7. Gilligan’s Island (1964–1967)

Seven castaways stuck on a desert island somehow had unlimited costume changes and elaborate equipment but couldn’t fix a simple boat.

The show’s cartoonish logic and paper-thin character development epitomize old-school television simplicity.

Each character represented a single trait or stereotype rather than a complex human being.

The Professor could build a nuclear reactor from coconuts but not repair a boat hole.

Mary Ann and Ginger existed primarily as romantic interests with minimal personality development.

Modern audiences raised on prestige television expect layered characters and consistent internal logic.

Today’s viewers dissect plot holes and demand sophisticated storytelling with real stakes.

A show this formulaic and lightweight would struggle to find an audience beyond nostalgic older viewers.

Streaming platforms favor complex narratives over simple slapstick comedy.

8. Bonanza (1959–1973)

The Cartwright family ruled the Ponderosa ranch with authority that went largely unquestioned for fourteen seasons.

Classic Western tropes dominated every storyline, with limited attention to historical accuracy or diverse perspectives.

Native American characters appeared primarily as obstacles or exotic others rather than fully realized people.

Women had minimal roles beyond needing rescue or providing romantic subplots for the Cartwright men.

The show presented a romanticized version of westward expansion that ignored the violence and displacement involved.

Modern audiences demand more honest portrayals of this complicated historical period.

Today’s Westerns grapple with moral ambiguity and systemic injustice rather than celebrating frontier heroism.

A show presenting white ranchers as unambiguous heroes would face criticism for whitewashing history.

Contemporary viewers expect more nuanced exploration of power, privilege, and consequences.

9. Happy Days (1974–1984)

Nostalgia for the 1950s fueled this show’s entire existence, presenting an idealized America that never really existed.

The Cunningham family faced no serious problems, lived in spotless comfort, and embodied wholesome values without complexity.

Every conflict resolved neatly within twenty-two minutes with a heartwarming lesson.

This sanitized version of the past ignored the era’s racism, sexism, and social turmoil.

Modern audiences recognize how such portrayals romanticize a time that was actually quite difficult for many Americans.

Today’s viewers demand acknowledgment of historical complexity rather than fantasy versions of the past.

Contemporary television embraces moral ambiguity and difficult questions instead of simple answers.

A show this safe and unchallenging would seem boring to audiences raised on antiheroes and complicated narratives.

Happy Days represents a television philosophy that no longer resonates.

10. Leave It to Beaver (1957–1963)

The Cleaver family represented suburban perfection with their spotless home, well-behaved children, and complete absence of real conflict.

Ward came home from work to June’s pearls and freshly baked cookies while the boys learned gentle life lessons.

This idealized nuclear family model feels completely disconnected from modern reality.

No family today lives this way or even aspires to this level of sanitized perfection.

Single parents, blended families, working mothers, and diverse household structures reflect actual American life.

The show’s rigid gender roles and unrealistic family dynamics seem quaint at best, harmful at worst.

Modern family sitcoms embrace chaos, imperfection, and genuine struggle rather than presenting unattainable ideals.

Today’s audiences want to see themselves reflected onscreen, not some fantasy version of domestic life.

Leave It to Beaver belongs firmly in its own era.

11. MASH (1972–1983)

This Korean War comedy-drama earned respect for tackling serious themes through humor and heart.

However, some jokes haven’t aged well, particularly those involving women and authority figures.

Nurse characters often faced objectification and harassment treated as harmless flirtation rather than workplace misconduct.

Hawkeye’s constant romantic pursuits of nurses would register as inappropriate behavior by today’s standards.

The show’s treatment of female characters as romantic conquests feels uncomfortable through a modern lens.

What seemed like charming rogue behavior in the 1970s now looks like harassment.

Despite these issues, MASH remains more watchable than many shows from its era because of its antiwar message and emotional depth.

But a modern remake would need to completely rethink how it portrays gender dynamics and professional relationships.

The show’s progressive politics don’t excuse its regressive gender attitudes.

12. The Love Boat (1977–1986)

Every week brought new passengers and new romantic entanglements aboard the Pacific Princess cruise ship.

The formula never varied: three separate storylines involving predictable romance, misunderstandings, and happy endings.

This episodic structure feels painfully shallow compared to today’s serialized storytelling.

Female characters existed primarily to fall in love or be pursued by male passengers.

Gender stereotypes drove most plots, with women seeking romance and men seeking conquest.

The show treated relationships as simple puzzles to solve rather than complex human connections.

Modern audiences expect character development across seasons, not reset buttons after every episode.

Shows like The Love Boat represent an outdated television model where nothing really matters or changes.

Contemporary viewers want stakes, consequences, and emotional investment that episodic romance plots cannot provide.

13. Sanford and Son (1972–1977)

Fred Sanford’s junkyard business and constant scheming made for groundbreaking television in the 1970s.

The show gave African American characters complex personalities and starring roles during an era with limited representation.

However, its reliance on stereotypes and abrasive humor presents challenges for modern audiences without proper context.

Fred’s insults and schemes, while funny, reinforced certain negative stereotypes about Black families and businesses.

The show walked a fine line between authentic character portrayal and caricature.

Today’s viewers might struggle to distinguish celebration of Black culture from exploitation of stereotypes.

Without understanding the show’s historical significance and context, modern audiences might miss what made it revolutionary.

The comedy style feels dated, and some jokes would definitely raise eyebrows today.

Sanford and Son deserves recognition but would need careful framing for contemporary viewers.